State of Pitching (Part I): The Rise of the ‘Opener’

The Art of Pitching—A Brief History

The Art of Pitching—A Brief History

When the National League opened for business in 1876, teams began with small rosters of perhaps 11 or 12 players on the entire team. And those who were starting pitchers pitched when they were not playing the field, and they pitched. There weren’t rosters of 13 or 14 pitchers as there are today.

The initial idea of a pitcher was a position player who was pitching today’s game. A player who stood in the center of the diamond, toed the rubber, wound up and hurled underhanded bee-bees to the catcher. This player was the starting pitcher, penciled in to pitch an entire game, and that’s what he did. Throw nine innings or 16 innings, or whatever was required to complete a game. That’s why pitchers threw as many as 400 or 500 innings in a season in the earliest years of baseball, and complete games defined 19th century baseball.

Starting pitchers started and finished games. No one replaced them, unless they were injured and could not continue.

In 1903, Bancroft “Ban” Johnson cleaned up his Western League of teams cobbled together from several of the ragtag leagues competing with each other in the first quarter century of the game, renamed them the American League, and negotiated a new combination with the existing National League, called Major League Baseball. This added twice the number of players into the association, and as a result, the game began to change.

Still, even in 1904, starting pitchers finished 88 percent of their games. Almost nine out of every 10. It was still a starting pitchers league. But within 10 years, in 1914, complete games declined to 62 percent. And by 1920, the percentage of complete games fell to 57 percent. That’s six out of 10. Who was pitching those other innings? Someone. Mind you, complete games were still good compared to the two percent of games completed in 2014, and perhaps even less than that today. Two out of every 100 starts. Quite different than 88 out of a 100.

It’s no wonder, that in today’s game—with the adage “you can never have enough pitching” still being voiced by general managers—finding pitching diamonds in the rough is not easy. And the competition for starting pitchers is fierce.

So, something had to be done.

The Art of Pitching—2018

By necessity, some teams, without the financial resources to purchase top pitching skills, rethought their pitching stocks and decided to send out relief pitchers to “open” games. Instead of spanning the world to find a fourth or fifth starter. Teams wanted pitchers who could throw one or two effective innings to start the game. They began to be called “openers.”

Openers were pitchers once viewed as starters who could not cut the mustard, but were now viewed as assets who could contribute to the solution of every team’s greatest problem: how to secure the 4,374 outs spread out over 1,458 innings and 162 games in a season. The immediate question: Can they get six outs to start a game?

Baseball scribes write about this trend in newspapers across the country. Analyzing it. Discussing its viability.

Why? Because it’s different, and, lo and behold, effective to send out a blazing lefty to open the game and follow him with another hard-throwing right-hander, thwarting the effectiveness of the right-handed platoon strategy. Many right-handed hitters who face lefties, mash them, but against a righty, some platoon hitters are befuddled, and less likely to do damage.

Pitchers who contribute quality innings to a team’s effort are valued differently than those called on for mop-up duty. But some baseball columnists writing about this emerging trend, call this opener, the “bum of the game.”

So, is this opener strategy effective?

Yes.

The Tampa Bay Rays chose young hurlers—unheard of pitchers—who threw faster than the wind to be their openers in the first inning. Not only were they effective, but they became an important reason for the team’s surprising performance during the 2018 season. A team that wasn’t even expected to find the .500 plateau in the tough American League East finished 18 games over .500 at season’s end. And, to top it off, they became a threat to make the playoffs the last month, just falling short.

Major League Baseball does not easily change conventions. This statement has been proven true over many years. Unless there’s a threat to revenue (the reason behind the introduction of the DH in 1973) or some other competitive imbalance. But over the last three or four seasons, the importance of the bullpen has begun to dwarf the importance of average starting pitchers, since hardly any starters go nine innings anymore. That’s why relievers are no longer just bodies down there. Guys to mop up. Pitchers who throw high-90s gas and filthy secondary stuff.

So, the question has become, why not use these weapons when the game’s on the line? Why not wield them in key situations to negate effective hitters?

Perhaps the question of why should be considered.

Why have openers become a big deal? Why are the definitions and strings attached to these terms evaporating off the pitcher’s mien?

Very simply, some teams cannot afford to add significant payroll (think of the cost of a quality starting pitcher in the free agent market) during or after a season. A trade for a top notch pitcher is also extraordinarily costly, especially if the player is controllable for several years.

For example, this past trading deadline, the New York Mets refused to trade any of their three top starters, no matter the offer. This is not to say that they should have made any of the three trades, it’s merely that they decided to keep their assets. It’s equally possible the Mets do not have the depth of pitching quality in their depleted farm system, and so do not have valuable pieces to “open” ballgames.

So, questions like, “Who can open?”or “Who’s better at working in high-leverage situations when the game’s on the line?” have become important pieces of information to help teams decide how to deploy their pitchers to maximum effect.

So, small market teams that don’t have the resources of the New York Yankees or Los Angeles Dodgers or a few other large-market teams, have devised a strategy to do an end-around expensive starting pitching by reaching into their own repertoire of major and minor league pitchers to find quality pitchers who can open games.

Tampa Bay, Oakland, Kansas City, Miami and other small-market teams can now cobble together a starting rotation out of their own assets, which they’ve always done, deciding whether they want starters or openers. It’s possible, if these teams find quality fourth or fifth starters within their organizations, they might return to the conventional mode of starting pitching and use their openers in different ways.

But all these options connote that teams are seeking more efficient ways of using their assets. They are not locked into old habits. Perhaps they might go the starter route, but start the game with the opener to extend the life of their starter into the seventh or eighth inning. In short, pitchers are pitchers in this model. Forget reliever, starter or even opener. They can be used wherever the manager wants to use them.

Mix and match, so to speak. After all, the game is ultimately about getting outs in key situations when runners are on base and a pitcher has to retire a tough hitter like a David Ortiz, Joe Morgan, Edgar Martinez or Mookie Betts. To keep the game tied, to maintain a lead or to limit damage so a team can fight back an inning or two later.

This theory of interchangeable pitching is not new, in fact it’s been used intermittently over 100 years of baseball, and then abandoned as though it had never been tried before.

Does anyone remember Firpo Marberry of the 1924 Washington Senators? Or Jim Kostanty of the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies?

Does anyone remember Firpo Marberry of the 1924 Washington Senators? Or Jim Kostanty of the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies?

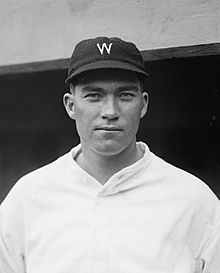

Firpo Marberry was a hard-throwing rookie on a talented Washington pitching staff that included “The Big Train,” Walter Johnson. Even though Johnson excelled, Marberry was perhaps the key member of the Senators. Why? Because he pitched so many important innings during the season as both a reliever and starter, he was instrumental in their pennant-winning season. And then he started game three of the World Series and relieved in games two, four and seven, securing the outs that helped Washington thwart the pesky New York Giants in seven games.

So, Marberry’s 1924 season was unusual. Yet, no one in baseball seemed to notice they could emulate the way Washington used the rookie. For some reason 26 years passed before another pitcher was so effective that his manager pretended he was Firpo Marberry.

That pitcher was Jim Kostanty of the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies. He won the National League MVP Award and was instrumental in the Phillies’ pennant-winning season. Pitching exclusively out of the bullpen, Konstanty threw 152 innings over 74 appearances (in a 154-game season, meaning he pitched in almost half the Phillies games) and sported an NL-leading ERA of 2.66.

The Phillies over-pitched Konstanty in 1950, using him in many back-to-back games (including quite often in both games of a doubleheader), and even pitched him 10 innings in relief in one game. Such usage is unheard of today, when the best starters go only seven or eight innings. Though overuse may have been why Konstanty never repeated his one great year.

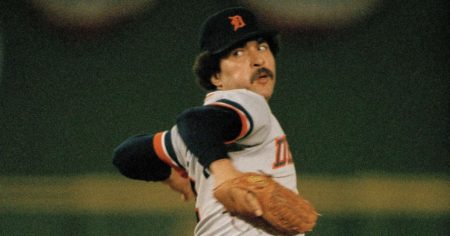

Regardless, baseballers still did not see Konstanty as a weapon they could fashion for themselves. Ten years later, a few pitchers threw more than 100 innings again. Dick Radatz and Stu Miller were among the best in the 1960s. While, in the 1970s, Goose Gossage, John Hiller, Tug McGraw and Aurelio Rodriguez enjoyed great seasons of more than 100 innings. And, of course, Willie Hernandez had his season for the ages in 1984 when he hurled 140.1 innings for Detroit and led them to the World Series, winning the MVP and Cy Young Awards.

In Part Two, this trend in pitching is explored further.