Ferocious Uppercuts (Part III): Baseball Needs Many MORE Carlos Santanas

Part III of a three-part series (See Part I, Part II)

Part III of a three-part series (See Part I, Part II)

Today, teams rely on analytical information to make player decisions so they can avoid chasing home-run hitters they shouldn’t. Like Albert Pujols or Chris Davis.

The effects of age on player performance are now better understood. So, many teams are reluctant to pursue older players when they can acquire younger players in their primes who cost less and offer greater production for the dollar. Players who can positively impact a baseball team for years to come.

So, players who hit 40 home runs the season before, and are now free agents, are looked upon with suspicion. Just because they did it at age 30 does not mean they will replicate their performance at age 31 or age 32. With brilliant contrarian swagger, Boston gambled on JD Martinez, waiting until the beginning of spring training in February 2018 to offer him a contract.

Martinez signed a five-year $110 million dollar contract for his age 31 season because his age 30 season was spectacular. Splitting time between the Detroit Tigers and the Arizona Diamondbacks, he put up an OPS of 1.066 (which is Hall of Fame level production) and a WAR of 3.8, meaning he was a valuable player for both teams. Despite that apparent value, Martinez was “only” offered five years.

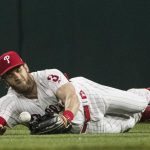

Carlos Santana signed with Philadelphia before Christmas and was considered smart because he accepted a three-year, $60 million year contract for his age 32 season when many others waited and waited for contract offers that were never offered.

So, some sluggers with special skills, like Martinez’ 1.000+ OPS and Santana’s walk percentage (15.3% for his career, against a 16.6% career strikeout rate), were offered contracts, but of relatively short duration.

Other home-run hitters like Mike Moustakas, who may have expected a five-year contract offer in the range of $90-$100 million, instead received only a one-year offer of $6.5 million a season from his prior team, Kansas City, for his age 30 season. Moustakas had to be disappointed. Though $6.5 million a year is better than no offer at all, it should be noted that Moustakas had turned down Kansas City’s Qualifying Offer of $17 million only a few months before, so, by turning down the QO, he left about $11 million dollars on the table. Ouch!

While home runs are still highly valued in baseball, teams have shown they will no longer spend wildly on older, one-dimensional hitters, unless they offer other values. Like speed. Defense. On-base percentage. A high OPS. Or other intangibles teams value as winning variables.

The values of baseball are changing. If you listen closely to the conversation, you’ll hear many different threads about what’s happening and why. But no one definitive set of ideas has emerged other than sabermetrics (which has actually been around since Branch Rickey introduced some of the statistical concepts in the 1950s). And while it’s a more efficient barometer to judge player performance and value, informing many of the decisions general managers make as they best decide how to populate their rosters, it’s only in the last decade that these concepts have caught on.

This new precision is changing the way teams evaluate free-agents as well as the way teams approach the game, but it’s also draining the game of some of its excitement because of the suffocating defensive shifts and the endless pitching changes that slow the game to a crawl in the later innings. The analytics encourage managers to use the numbers to decide which hitters hit or cannot hit certain pitchers. And the hitters wait and wait for their pitch, fouling off the pitcher’s pitches until they get that pitch. The hanging slider. The curveball that doesn’t curve. The fastball that cuts the plate in half. Resulting in hundreds of pitches thrown every game. Fans waiting and waiting for something to happen. And what happens most often is a strikeout. There may be more strikeouts than hits this season. More strikeouts than singles this season.

Strikeouts deaden the pace of the game. And that is the problem. So many hitters strike out because they refuse to poke the ball into the outfield for a single. It’s a macho thing. So, they swing for the fences and meekly ground out to shortstop or strikeout. But what hitters want is another notch on their belt. More money in their contract. But as the players get richer, the game suffers.

The same way the game suffered during the Steroid Era of the 1990s when so many players were smashing balls over fences with the aid of an artificial agent in their bodies. Corrupting the essence and purity of the game. Even as home runs and strikeouts continued to corrupt the game. For the worse.

It’s no wonder that so many in baseball are looking for solutions. Now, the question is how MLB will adjust its sense of what is important in the game. What’s important? Home runs? Putting balls into play? Rallies? More and more pitching changes? More pitchers who throw 100+? There’s a sexiness to the numbers. To launch angles. To velo. To lots of home runs. To radar guns that punch out three-digit numbers.

But is there a sexiness to slower games? Is there a sexiness to long lulls in action? The game has to decide what it values and what it wants to value long-term. Unfortunately, as in most institutions, value usually equates to money. If it’s important, it pays well. So, perhaps the only way to change the game, and it will take time, is to start paying real dollars for skills that have been devalued for too long. Skills that move the game along.

In a way, the free-agent signing of Carlos Santana last winter (2017) by the Philadelphia Phillies was intriguing. He was signed because he walks. A lot. Much more than the average player. His OBP this year is .358. Not .400, but he serves as an example to the younger Philadelphia players how to work an at-bat. How to get on base. And his WAR is 3.8, so he is still a valuable player. Even with a .784 OPS. Analytics understand that walks are part of a winning strategy. Teams that walk a lot, win. So maybe more players like Santana should be rewarded more for their winning skills. Although $20 million a year for three years is not a pauper’s recompense. And perhaps that will serve as an example for players who hardly walk at all, to change their approach at the plate, make the game more interesting. Hmm.