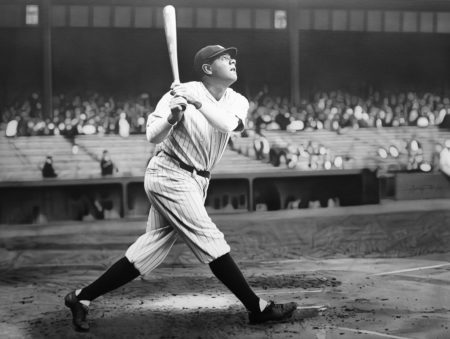

Ferocious Uppercuts (Part I): In the Beginning, Babe Ruth Swatted, Loudly

Sometimes I don’t understand MLB. It seems to be unable to see the timelessness and beauty of its game being despoiled by the unprincipled, ferocious uppercuts. Uppercuts that either result in a fly ball soaring over the wall, or more often than not, strike three.

Sometimes I don’t understand MLB. It seems to be unable to see the timelessness and beauty of its game being despoiled by the unprincipled, ferocious uppercuts. Uppercuts that either result in a fly ball soaring over the wall, or more often than not, strike three.

The ferocious uppercut is the root of the problem. And why should players worry about adjusting their swing to hit the ball through the vacant side of the shifted infield defense? Or even put the ball in play to move the runner over? Or stroke a measly single when the entirety of MLB is screaming at them to do one thing. Players get the message. They understand launch angles. Velocity. Fly balls. Distance. They hear those words and think one thing: home run.

A few strikeouts, so what. An out’s an out, right? You’re going to make 400 of them a season, so what if it’s a strikeout? (Of course, if the ball was hit and moved the runner over or an error’s committed, it would create action and excitement, far more than the strikeout does.)

And suppose you hit a home run? Hit enough of them and that’s more money in your paycheck next year. That’s right, there’s big money behind the home run. Today. Players know this. That’s why they’re working on their ferocious uppercuts. To launch fly balls over fences in even the least hitter-friendly ballparks. So, home runs and strikeouts not only deaden rallies (they both end rallies, but in different ways), but are the main culprit why today’s game has slowed down.

And you still ask, why?

The success of Major League Baseball, ever since the Black Sox Scandal of 1919, has relied on the long ball.

Annoyed by their pay and other small nuisances, Charles Comiskey, owner of the White Sox, dumped on his players; some members of the White Sox accepted thousands of dollars to throw the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds.

That same year, Babe Ruth finished his last season with the Red Sox hitting 29 home runs, breaking the MLB home run record as a pitcher. Even though he was overshadowed by the scandal, baseball took notice. Babe Ruth unveiled his magnificent 13-year saga that would change baseball and propel it into its next era.

Ruth showed he was one of the first hitters who understood how to mash the new cork-centered ball, first introduced in the major leagues in 1911. That Ruth’s blasts gyrated out of ballparks was because he smacked them the right way. And he was smacking it the right way.

Beginning in 1920, his first season with the Yankees, Ruth stopped pitching and concentrated on what he had begun to do the season before. The season when he hit three times as many home runs as the man closest to him, Benny Kauff. And that was walloping massive fly balls over the right field wall in Fenway Park.

In his first season with the Yankees, Ruth swatted 54 home runs in the Polo Grounds, and most of the baseball world exploded in excitement. Suddenly, games could be won on one swing of the bat.

However, as Brian Kenny opines in his book, Ahead of the Curve, not all of baseball was thrilled. Kenny writes, “The greatest hitter in the history of the game, as he began dominating the game, was routinely slammed by the ‘purists.’ John McGraw, Ty Cobb, and the influential Henry Chadwick thought the Babe was ruining the game.”

It’s no wonder the Yankees suddenly became electric. Within three years, a new Yankee Stadium opened in 1923.

In 1925, Lou Gehrig joined the Yankees and hit 20 homers his first season. Kenny argues that Ruth and Gehrig gave the Yankees a competitive advantage over every other team in the majors until Ruth slowed down after the 1932 season.

So, as Ruth and Gehrig launched home run after home run, despite what the “purists” voiced, the baseball world watched closely. They saw ferocious uppercuts unseen before. And in the right place, the new cathedral of major league baseball: Yankee Stadium. So, baseball already popular, was on the upswing.

By 1936, only a year after Babe Ruth’s final dismal cameo with the Boston Braves and his retirement from baseball, Joe DiMaggio joined the Yankees. And while he was not a home-run hitter, his all-around game propelled the Yankees to win the next four World Series (1936-1939), as they became less dependent on Babe Ruth and his mighty wallop.

It’s no wonder that as the decades of the ’30s and ’40s approached, home-run hitters seemed to be on every team. Rogers Hornsby. Jimmy Foxx. Lou Gehrig. Mel Ott. Hank Greenberg. Ted Williams. Johnnie Mize. Chuck Klein, Stan Musial, Ralph Kiner and many others. The rush was on to smack the ball out of the park, but because of the Reserve Clause really big money would have to wait.

There’s a story that, in the year Ralph Kiner led all of major league baseball with 47 home runs in 1950, he went in to ask for a raise at the end of the season. Not an unusual request for an employee who’s had an outstanding year. However, he was met by the calm, stoicism of Branch Rickey, who rose from his desk, stood in front of Kiner, and in his deep, husky voice, told Kiner the Pittsburgh Pirates finished last with him, and they could finish last again next season, without him. And then Rickey proceeded to cut Kiner’s salary. Had the Reserve Clause been repealed, as would happen a quarter of a century later, Rickey would not have been able to act so imperiously, and Kiner might’ve gotten his raise.

So, the home run became the engine that supercharged baseball and propelled it forward. Over the coming seasons, it would become even bigger.

(See Part II)