The Game that Changed Baseball—Part II

This is the second installment of a three-part series. See Part I.

This is the second installment of a three-part series. See Part I.

Brooklyn took the field and quickly Cincinnati led 3-0, but a few poor fielding plays (remember there were no baseball gloves at that time, so players fielded balls with their bare hands, making errors much more commonplace) and Cincinnati’s lead evaporated as Brooklyn took a 4-3 lead after six innings.

The New York Tribune reportedly wrote that while the score was only 5-5 after nine innings, the excitement of the struggle was “unbearable.”

Harry Wright rejected the Atlantic’s offer of a draw after consulting with Henry Chadwick, the Englishman turned New York sports writer and baseball statistician, who was in attendance. Chadwick told Wright that the game must be decided in extra innings.

Chadwick also whispered in Wright’s ear he had heard gossip that a large bet had been placed on the game and it wouldn’t pay off if the teams remained tied. Chadwick, an astute observer of the scene, had not bet on the game himself, but he understood why Boss Tweed was waving his derby and clamoring so vehemently that Brooklyn show some guts. Because if the game remained tied, the 300-pound Sachem of Tammany Hall and his cronies stood to lose tens of thousands of dollars. So, all sides agreed they’d play to a conclusion.

After threats in the 10th inning, the Red Stockings broke through in the top of the 11th to take a 7-5 lead. They took the field in the bottom of the inning a confident nine, ready to record their 28th victory in a row.

Bottom of the 11th

As the inning was about to start, Boss Tweed jumped out of his seats in the front row (he needed more than one) near the Brooklyn bench, making a spectacle of himself quivering his rotund belly as he threatened the integrity of his suit pants swinging his arms wildly every which direction as he screamed profanities at the Red Stockings, cursing their mothers, among other choice incantations while the light-hitting, diminutive infielder Charlie Bastian swung several bats on his way to home plate to lead-off for Brooklyn.

The Red Stockings’ pitcher, Asa Brainard, bent over slightly as he peered into home plate, digging his feet into the pitching box, studying Bastian’s nervous twitter. This had been a tough game for the usually reliable Brainard, and it was about to get worse. He could not foresee the failure of his defense that was about to bedevil him.

It started simply enough, Bastian got on base but the next batter, Brooklyn’s Joe Start, smashed a long drive over the head of Cal McVey in right field that rolled to the wall where the crowd was sitting. McVey ran back to fetch the ball but, unlike baseball today, it had bounced into the sea of fans lining the outfield wall from foul pole to foul pole. McVey scrambled to find the ball but as he did he was attacked by several exuberant Brooklyn fans who knocked him down and delayed his throw into the infield, allowing Start to reach third base on the interference (which was legal then). As the ball made its way back to the infield the score became 7-6, still in Cincinnati’s favor. But Brooklyn wanted more.

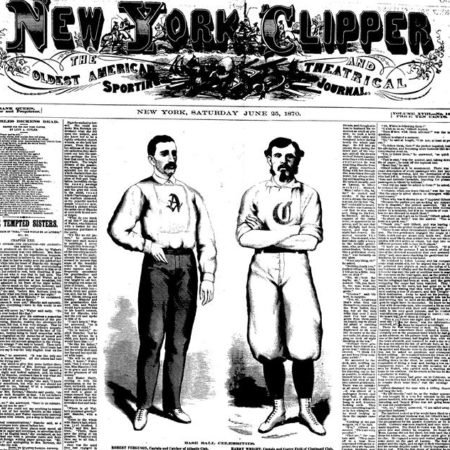

Two Brooklyn singles later, the second by Bob Ferguson—the great Brooklyn captain who batted left-handed this time after having batted right-handed earlier in the game against the Red Stockings’ diminutive lefty, Count Sven Josephson, the first time a batter had ever switch-hit in a game—and his rope into right-center field tied the score 7-7.

A wild pitch later and the winning run, Ferguson, was poised on second base, hoping for one more crack of the bat and then, the exuberance of victory.

Boss Tweed offered more gesticulations and screamed in delight, cupping his pudgy hands together as though he was a left-handed hitter about to wallop a meatball out of the park. But now it appeared that not only Brooklyn could win, but Tweed could cash in as well.

Brainard turned, took off his cap, mopped his brow, and when he faced home plate, the Red Stocking catcher stood inches away in the flat pitching box. The two men discussed the next batter, the Atlantics’ pitcher, George Zeittlein. Conversation over, the catcher trotted to his position about 20 feet behind the batter (catchers would not squat near batters for a while, until protective equipment was developed). Brainard flipped the soiled, tattered ball in his right hand—the same ball that had been used the entire game—contemplating an escape from the predicament.

As Brainard delivered, there was a sharp crack. Zeittlein scissored a grounder to shortstop, what seemed an inning ending double play ball. Brainard had thrown the right pitch. He expected a 12th inning. But …

George Wright cleanly fielded the grounder and tossed the ball to Charlie Sweasy at second base. The toss was slightly wide, and in those few precious seconds of bobbled futility, Sweasy mishandled the perfect season, dropped the ball, and just like that Ferguson scored the decisive run.

A swell of pandemonium broke out all over the field, matched only by the jubilant urge of the fans to mob their Atlantics as they charged the field from every direction to celebrate victory.

The Streak Is Over

The Streak Is Over

A year-and-a-half winning streak that had run 84 games had come to an end. Cincinnati was now 27-1 in 1870. But the feeling inside the stadium was that a giant had just been vanquished. Boss Tweed stood mesmerized, for the first time all game he was quiet, but pressing flesh with the men on either side of him as he smiled like a Cheshire cat.

George Wright languished at shortstop, immobile. He lifted his head, aware that his mistake had just cost Cincinnati its winning streak. Everything. He glanced around the stadium and cursed the chaos of sudden victory. Brooklyn fans coming from all angles carrying Atlantics around the infield on their shoulders in a wild celebration and the sounds, the decadence of dissonance, rung his ears with the sounds of defeat.

This ordinarily brilliant player glared at the discombobulated movement, every run and jump and trot and clutch joined in a chaotic togetherness just like a Jackson Pollack abstraction (which, of course, had not been painted yet). What Wright felt were the occasional jostles, the hands on his body. As if he was not here in Brooklyn on this field. He could’ve been a tree. But he was there on the wrong side of the 8-7 loss. After 84 consecutive victories, what so bothered him was the knowledge that losing was not the business he wanted to be in.

Not once. Not ever.

Up next: The Aftermath