The Real Strike Zone: Swinging for the Fences

Strike zones have come and gone over the years to suit the temper of the game. That’s because the strike zone has been a tool to tweak the hitting zone, adjusting offense as per the perceptions of MLB.

Strike zones have come and gone over the years to suit the temper of the game. That’s because the strike zone has been a tool to tweak the hitting zone, adjusting offense as per the perceptions of MLB.

This imaginary grid, the strike zone, exists beside every hitter that steps into the batters’ box. It affects the way hitters select pitches to hit and pitchers tactically attack hitters.

Today, however, the strike zone is not as imaginary as it once was. It’s become a visible target. Pitchers deign to fool hitters into swinging at the coiled snakes and butterflies they throw up to home plate. Anything to keep the red-laced orb out of the strike zone.

Nope, the strike zone wasn’t always this way. But this is what it’s become in 2019.

Ted Williams and the Strike Zone, 1960s Style

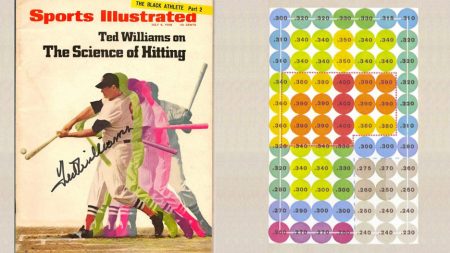

Ted Williams wrote a well-known book on hitting and the strike zone in the late 1960s. His ideas were popularized in a Sports Illustrated issue published July 6, 1968. That cover showed five different colorized points of Williams’ majestic swing arc superimposed over each other.

Presumably, the book was written to provide players (of all ages, including major leaguers) a way to emulate Williams’ disciplined approach to hitting.

The Sports Illustrated article was published during the Year of the Pitcher, 1968—the year Bob Gibson of the St. Louis Cardinals won the Cy Young and MVP. His ERA was an austere 1.12. The same year that Denny McClain of the Detroit Tigers won 31 games, though his ERA was a more generous 1.96. He was the AL MVP that year.

Because of the sheer number of pitchers who had career years in 1968, MLB decided to act. Decisively. They turned around and took a giant step six years backward.

The strike zone was redefined to its pre-1963 shape and the mound was lowered from 15 to 10 inches high because by 1968 MLB was unsure whether anyone could hit the damn ball anymore.

Whereas, after 1962, the unspoken worry was, if Roger Maris, that’s Roger Maris, could hit 61 home runs in 1961, anybody could. The fact he broke Babe Ruth’s sacred single-season home run record of 60 home runs upset many purists. Imagine needing 162 games to hit 61 when The Babe only needed 154 to swat his 60. What chutzpah! So, the strike zone was tightened.

Not that MLB knew what it was doing because, soon enough—though fewer home runs were hit—bases on balls decreased, the dreaded strikeout increased and batting averages plummeted. All unexpectedly. The net effect was pitchers took control of the game and there was less offense. Ouch.

After the Year of the Pitcher, MLB was as mortified by the hydra it had created as by the lack of a savior who would slay the beast, behead it and replace it.

In the 1,619 games played that season, 339 shutouts were recorded. The heads were everywhere.

American League hitters posted a league-wide slugging percentage of .339 in 1968, the lowest percentage since 1915 and the dead-ball era.

So, hitters needed help.

Help! Ted Williams, Help!

Perhaps that’s why Ted Williams was convinced to publicize his theory of hitting. Inside the Sports Illustrated issue, there was a now-familiar picture of Williams standing beside a mock strike zone separated into 77 color-coded balls.

Eleven balls covered the length of the strike zone from top to bottom, while seven balls extended across the width of home plate. Each of the 77 balls was color-coded with a batting average superimposed inside the ball.

The darkest red balls were numbered .400 and occupied a sinewy loop in the heart of the strike zone. The lighter red, yellow, and light green balls that surrounded the deep red were also meaty offerings, though the numbers descended, .380, .360 and so forth.

Presumably, most of the hitters in 1968 were swinging at the gray, purple or dark green balls dotting the perimeter of the zone. No wonder they struggled to hit .250 and became accustomed to trudging back to the dugout.

Williams explained his theory of two strikes: I didn’t always swing for the fences. With two strikes I always told myself, ‘Meet the ball. Don’t try to pull.’ I wanted to be a good hitter. If I had gone for more home runs, I wouldn’t have hit .344 lifetime.

What Ted Williams couldn’t imagine was a day when the strike zone would lose its province. A time when hitters wouldn’t fear strikeouts. A day when hitters would swing for the downs no matter the count, strikeout and care less about the effect it had on their batting averages.

A day when his concept of the strike zone had become as antiquated as Al Barlick and Shag Crawford barking out strike three.

Regardless, in 1969, MLB had to intercede. Hitters needed help. The monster who slew the hydra was Commissioner Bowie Kuhn with the help of the MLB Rules Committee. Within four years, the American League adopted the Designated Hitter Rule. The baseball rock show had begun.

The Rock Show is A Changin’

Exit velocity. Launch angles. What?

Ted Williams did not write about exit velocity or launch angles in his book. Never needed them. But now with the latest uppercut wallops, the baseballese terms measure the effectiveness of today’s home-run swing.

Ted Williams assumed that any hitter who swung at pitches in the .400 or .380 or .360 hitting zones would hit the ball hard and generate consistent offense. Presumably hard enough to generate an effective exit velocity and if their launch angles were sufficiently acute, memorable home runs would ensue, like some of Mickey Mantle’s blasts.

But not every hitter was Ted Williams or Mickey Mantle. And, today, not many hitters choke up or cut back on their swings with two strikes to make contact. Even with the game on the line. They’re going for it. Nothing like a walk-off home run.

And, now, with a new analytical tool to measure performance, OPS (a statistic that merges on-base percentage with slugging), hitters’ batting eye and slugging power can be expressed in one number. An important stat since 1984 when The New York Times published the top ten OPS leaders in its weekly By the Numbers column.

OPS has changed the way management viewed hitters’ productivity. Sure, it’s great to hit .310, but if the OPS on that .310 is .648, that’s dismal production. Being a weak .300 hitter would no longer be enough. Being a .300 hitter with a .950 OPS implied a very productive hitter. Even better, if one hit .225 yet managed an OPS of .874, the OPS said forget the batting average, this batter has been productive. He’s driving the ball.

Pete Alonso, Difference-Maker

Pete Alonso of the Mets has struck out 28.9 percent of his at-bats as of July 12. But he also has clobbered 30 homers, pushed 68 runs across the plate and is hitting .277. That comes to an OPS of .999. It would be an act of lunacy if Brodie Van Wagenen decided to send him to the minors when he’s the best hitter on the team.

Fifty years ago, Alonso would be in the minors. He proves there is such a thing as dumb luck in baseball. If the Mets can strike gold, anyone can.

To further accentuate the point, Alonso’s Statcast values, his launch angle and exit velocity, place him among the top hitters in the National League. When he gets a hold of a pitch, he punishes it. And yes, he chases pitches occasionally, especially given the dastardly designer breaking balls pitchers throw to give cover to their 98 mile an hour fastballs. Which is why Alonso has struck out 95 times in 328 at-bats.

FanGraphs further shows that hitters swung at 30% of pitches outside the strike zone in 2014, according to pitch-tracking data, which was up from 27.9% in 2009.

That’s why teams are trying to find that one player who can make a difference, every game. Not by singling up the middle, but by banging balls off walls, or even better, over walls. And if they strike out, they strike out.

Remember Ronald Torreyes?

Remember Ronald Torreyes? He was an effective utility player with the Yankees in 2017 and 2018 before they traded him to the Cubs for a bag of balls (or so it seemed) in November 2018. He was a Cub for two days before being granted free agency. A week later he signed a one-year major league contract with Minnesota. Now he’s a Rochester Red Wing. Ugh.

His four year average OPS was .685. Despite the low number, he was a solid player with the Yankees who did all the little things to win ball games. Granted, Gleyber Torres is a much more powerful version of Torreyes. But it’s difficult to believe not one of the 30 MLB teams could use him. Especially since in 576 major league at-bats he has only struck out 80 times, for a 13.8 percent ratio. He puts the ball in play. But that by itself is not enough.

That’s why, in today’s game, the real strike zone is the bleachers. The cheap seats. That’s what hitters are aiming for. They don’t want to be the next Ronald Torreyes demoted to Triple-A because they can’t reach the cheap seats and their OPS is sub-.800.

The best hitters now strike out a lot, but then next time they step to the plate they flaunt their .800 plus OPSes at pitchers, waiting for a mistake they can launch into outer space. That’s today’s game.

Ted Williams was a great hitter. Hall of Famer. But his approach to hitting was his approach. Were any of today’s hitters the least bit interested in batting average they would beat the infield shift by pushing balls the other way when the bases are empty. Take the cheap single. Problem is cheap singles hitters don’t make big dollars. As for the lost art of bunting, yikes.

Home runs and strikeouts (for pitchers) yield long-term contracts worth millions of dollars. That’s what the strike zone means today.