Relievers, Wildcards and Apple Pie—Part I

This is Part I of a three-part series

This is Part I of a three-part series

Take a Deep Breath: Rethinking Relief Pitching

For years, the idea of using the best non-starter on a pitching staff to pitch only the ninth inning seemed a bedrock fundamental of baseball. After all, the ninth inning was the time to lock in a win, and who else but the starter (years ago), or the best reliever (today), would be on the mound. Right?

But today, the idea of when to use a reliever is changing.

“Openers” are relievers who enter the game in the first inning. Relievers called weapons are those who usually throw very hard, have excellent secondary pitches, and can not only strike hitters out, but make them look foolish at the same time. And while they may be closers, the time has come to think of them as movable pieces, weapons, not closers.

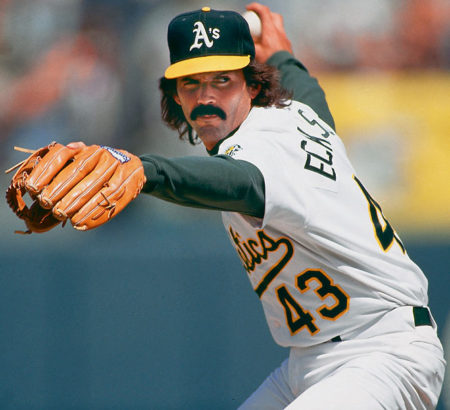

Until 1969, there was no such thing as a save, though there were relief pitchers who closed games. In 1969, the save became an official MLB statistic. And while there had been many effective relievers previously (remember the Hall of Fame knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm?), pitchers dedicated to pitching only the ninth inning and finishing a game did not become a reality until Dennis Eckersley, circa 1987. He was considered the first, true closer by the Baseball Hall of Fame, because he was used primarily for only one inning, the ninth, and usually started the inning.

And with the official save statistic now collected yearly by MLB, saves have become a well-paid category. And every team has a closer, even the bad ones.

Previously, other notable relievers were multi-inning specialists who entered the game earlier than the ninth. Think of Hoyt Wilhelm, Lee Smith, Bruce Sutter, Goose Gossage, Rollie Fingers and Sparky Lyle. They came into games in the seventh or eighth inning (or sometimes earlier) and would finish the game from whenever they entered.

The current idea of the reliever as a weapon derives from these earlier pitchers whose roles were not rigidly defined. And like so much in life that goes around and comes around, the new theory in baseball today is the realization that a team’s best pitchers need not be locked into static roles.

Why?

Because the difference between winning and losing can sometimes be a relief pitcher who holds the fort in the third or fifth inning. A pitcher who keeps the game close until his offense can retake the lead. And while it seems this is relatively new, look back into baseball history 100 years and you can find relievers who pitched early in games to thwart teams from winning in an early inning.

The definition of a pitcher, his role, and how teams have begun to realize that games can be saved in the fourth or fifth inning, is changing the way teams are using pitchers. It can be argued that even openers are an offshoot of these ideas. Want to win the game, disrupt the timing and rhythm of the offense from inning one? Use those initial pitchers to come at hitters from different angles and deliveries. Deliberately force hitters to adjust to different speeds and pitching styles. That’s the way it seems now. Obfuscation is the strategy.

But when I was growing up in the 1960s, and took for granted there would always be a Sandy Koufax, Bob Gibson, Tom Seaver, Jim Palmer and Jim Kaat on the mound, relief pitchers were nowhere near as prominent. Even though the percentage of complete games has dropped precipitously over the years, the Seavers and Koufaxes of the world were completing roughly half of their games, while Kaat completed approximately a third, in his prime. So, relief pitchers were not as critical as they are today.

But as complete games waned, the bullpens became stocked with more first-rate pitchers. Not the bodies who used to sit around waiting for a call. Take a look at Ramiro Mendoza.

Joe Torre used him as a weapon in the late 1990s. When Mendoza came into games, it seemed the Yankees magically disappeared from the field, even though I couldn’t hear the shouts of hocus-pocus-abracadabra. Their opponent’s innings seemed to dissipate quickly.

And even if the Yankees were behind, once Mendoza entered the game, it seemed they always had a good chance to catch up, even win the game. Mendoza was not throwing 100. He was pitching. Hitting the corners. Movement and location were his forte. Done quietly.

What I never considered were the number of innings Mendoza pitched. I knew Torre brought him into the game whenever necessary. As if Mendoza was a Swiss Army knife. He was that adaptable. He could pitch in any inning, or it seemed that way. There was no set pattern of usage. Mendoza came into the game when he was needed. That simple.

Except he threw more than 100 innings four of the six years he was a Yankee.

So, against this backdrop, last Wednesday night, the American League Wild Card game was played at Yankee Stadium (of the very short porch in right field) in New York. I paid attention to how the pitchers were used.