Baseball Magic, Sixties Style

A friend once asked me why I loved baseball so much as a kid. “Baseball magic,” I said.

A friend once asked me why I loved baseball so much as a kid. “Baseball magic,” I said.

“What’s baseball magic?” she asked.

I thought about the idea for a few moments. What was baseball magic?

Several thoughts came to mind.

Admittedly, the baseball games I’m thinking about were contested more than half a century ago. So, the memories have wizened.

Furthermore, unlike today, I read about the game. Or listened to it on the radio. Few games were broadcast on television, and there was no such thing as ESPN. No SportsCenter show of replays and game action playing hour after hour every evening. No cable television.

Just the darkness of night to dream about the exploits of heroes on baseball diamonds all over the country. Getting ready for the baseball magic tomorrow.

The Box Score

When I was left with box scores in the mornings, my imagination ran wild enough to make the numbers come alive. Who did what when? Who had a great game and who didn’t? What baseball magic did I miss?

I’d scour box scores posted every morning in the local newspaper and think of fantastic plays. Impossible hits. Curveballs that could not be hit. Pitchers who threw too many home runs. Majestic catches. Players running into walls. All the actions that might’ve happened. And those fabulous possibilities that might never have occurred.

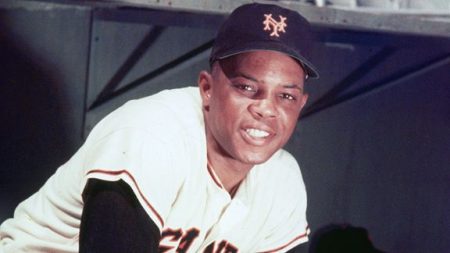

So, when I read that Willie Mays went four-for-six with two home runs and five RBIs, I remembered the Giants once played in New York. Or when Horace Clark struck out four times, I longed for Pete Rose or even Joe Morgan to patrol second base for the Mets.

Other times, I’d see that the crafty Bill White went three-for-four with a walk and wish he had been traded to the Mets. I even thought about how nice it would be if the Mets won more games with Julian Javier at shortstop rather than Ed Bouchee.

(As you might be able to tell, I had become a die-hard Mets fan growing up close to the new Shea Stadium. I learned quickly that eternal suffering was what the Mets demanded of their fans).

I saw players rounding the bases or sprinting after line drives or bobbling grounders behind second base as the tie-breaking run scored. I tried to imagine these different scenarios and the shape of a game. How each game unfolded differently.

I knew almost all the players by name, even though MLB expanded from eight to 10 teams per league in 1961.

Plus, because the Reserve Clause was still in effect, there was less player movement. Team’s remained essentially the same from year to year.

So, when Hank Aguirre, a tall, lean left-handed reliever for the Detroit Tigers in the 1960s (actually 1958 to 1967) appeared in a box score, I could see his windup and the way his ball broke when it swerved across home plate and batters flailed unsuccessfully at his pitches.

Or I could imagine the short, fireplug of a left-handed reliever jumping over the low bullpen fence in right field with his jacket slung over his shoulder. That was how the Yankee fireman of the early ’60s, Luis Arroyo, loped to the mound in Yankee Stadium to begin his warmups at the end of the game he was about to finish. Saves had yet to be invented.

Or, there was a time when my grandfather took me to a Yankees game in the early 1960s and sitting on the subway train with us were Al Downing, Bill Stafford and Rollie Sheldon, three younger Yankees pitchers to whom we said hello. I recognized them immediately and, for 10 or 15 minutes, couldn’t stop looking at them. I’ve never forgotten those few moments. And, of course, a decade later Downing gave up number 715 to Henry Aaron in Atlanta. As a Dodger.

Nor did I forget the masterly performance of Mickey Lolich as he unwound his bulky frame in the 1968 World Series with such a circular spring that his pitches hurtled toward home plate with a precision that baffled hitters. The slope of his curveball. The oomph of his fastball as he sneaked it past the befuddled St. Louis Cardinal hitters often enough to pitch three complete-game victories, including outdueling Bob Gibson in the masterful seventh game of the Series.

The Sixties

When I think back all those years, I remember a different game. Only two teams made the World Series until the playoffs began in 1969. Every game of the regular season meant something. Teams grew up together, in the minors and then the majors. The game was like masonry. Bricks and mortar. The foundation was solid. But change was coming

Ebbets Field was demolished in 1960. Roger Maris swatted 61 homers in 1961. MLB expanded from eight teams per league to 10 in 1961.

Maury Wills stole 104 bases in 1962. Sandy Koufax became the unhittable Hall of Fame pitcher he is remembered as in 1963. Branch Rickey died in 1965.

Marvin Miller became Executive Director of the MLBPA in 1966. Frank Robinson won the triple crown that same year as he led the Baltimore Orioles to their first World Series victory.

In 1968, it was the year of the pitcher and Carl Yastrzemski led the American League with a .301 batting average, while Pete Rose led the National League at .335.

Curt Flood refused a trade from St. Louis to Philadelphia in 1969, setting the stage for the beginning of the end of the Reserve Clause. MLB expanded from 10 to 12 teams per league in 1969. And the hapless New York Mets defeated the powerful Baltimore Orioles to win their first World Series in 1969.

Quite a decade. Quite a montage of images and bewitching memories that can be drawn upon to relieve distress and difficulty like an antacid relieves indigestion.

I’d snap my fingers and see Willie McCovey end the 1962 World Series with a scorching line drive pummeled into the glove of second baseman Bobby Richardson, leaving the bases loaded. That look of relief on the face of Ralph Terry, the Yankee starter, was also the look of a champion. I haven’t forgotten it.

Was this the age of baseball magic? Was there a power, somewhere, to make impossible things happen? I think so, or at least that’s the way I remember it.